Hunger Games 2019: Drought leaves 38,000 in need

Mbongeni Mguni | Friday July 26, 2019 12:47

Those involved in regional food security and forecasting, speak of a period known as “hunger season”, the critical period between September and March when the harvest peters out, at national and individual household level.

In an ideal world, each harvest continues a cycle from ploughing to reaping that ensures that the yields of the previous season tide national silos and households over to the next, comfortably skating over the “hunger season”.

Since at least 2014-2015, this has not been the case in Southern Africa, where the cruel El Nino climate phenomenon has meant that of the four cropping seasons since then, only one has been unaffected by a debilitating drought.

In that period, Botswana – particularly the southern regions – has experienced record droughts and many firsts, from the historic drying of Gaborone Dam, to the highest temperature in 46-years, longest series of heatwaves and the decimation of arable farming activities.

The immediate past cropping season has been no different.

In April, Mmegi reported that two thirds of crops planted around the country, largely by subsistence farmers, had wilted due to drought, while livestock deaths were rising.

The harvest was expected to be bad, but not as bad as a regional report released this week by SADC shows.

Going by the report, hunger season in 2019 will be a dicey affair for the region, where 41.1 million citizens are facing food insecurity.

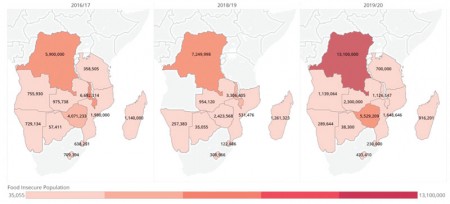

According to the report, 38,300 Batswana face in adequate access to food this year, up from 35,000 last year. Countries with the largest numbers of the food insecure include South Africa at 13.7 million, the DRC at 13.1 million and Zimbabwe at 5.5 million.

For many countries in the region, this year’s food insecurity is not just about the 2018-2019 season, but is actually the culmination of many bad cropping years.

The cycle that helps citizens skate over hunger season has been broken.

“Households are expected to exhaust their food reserve crops within zero to three months, compared to the average three to five months resulting in significant consumption gaps, especially from October 2019 onwards,” reads the SADC report.

“Much of west and central Southern Africa recorded their lowest seasonal rainfall since at least 1981.

“Rains were delayed and erratic, resulting in reduced area planted, poor germination and wilting of crops, (while) poor grazing and water conditions also affected livestock production.”

The SADC report, produced each July after the collation and sharing of data amongst member states, details the vulnerability of the region and countries. The report details recommendations for the immediate situation and future resilience.

“It is recommended that governments and partners urgently assist food insecure populations with food and/or cash based transfers.

“Emergency livestock supplementary feeding is also critical to save breeding herds. “Emergency establishment of community watering points for livestock and crops should be prioritised.

“Shock-responsive social safety nets should be scaled up to protect the vulnerable from recurrent severe climate-related shocks.

“Special attention must be paid to address the additional burdens faced by women and girls.”

Countries like South Africa, Namibia and Botswana traditionally dig into their reserves to cover their food insecure populations.

For the majority of the 41 million, however, the annual SADC report is not just a situation report, but also a clarion call for aid.

That assistance is not always forthcoming, as the repetitive droughts and competing crises across the continent, have worsened donor fatigue over the years.

Even with healthier reserves, Botswana is feeling the pinch of the successive droughts.

This year, the country will spend the most it ever has on drought relief, at about P1 billion.

Clerk of Cabinet, Ontiretse Letlhare, broke down the numbers for Mmegi this week:

P659 million for the provision of a second meal for primary school children

P136 million to help farmers pay back loans to state-owned agricultural lenders

P102 million for a livestock feed subsidy, which has also been raised from 25% to 35%

P50 million to beef up the Strategic Grain Reserve, the country’s cereal buffer

P18 million for urgent relief packages in areas worst affected by drought

P4.4 million for direct feeding of infants at public health clinics

Over the years that El Nino has blighted local fields and kraals, government went from paying P445 million for drought relief in 2014-2015 to P856 million last year.

“The main reason these amounts are going up is the intensity of the drought,” Letlhare explained.

“A good example is to look at the agricultural credit guarantee scheme where this year we are saying government will cover farmers up to 85% for their loans.

“Last year, government only covered 30%. “The officials involved on the ground make an assessment of the intensity of the drought and look at the quantum of assistance that will be required.”

Batswana, therefore, will skate through this year’s hunger season, but the situation is becoming increasingly unsustainable.

Former agriculture minister, Patrick Ralotsia, previously told Mmegi the centre would not be able to hold forever. “We simply cannot afford to keep doing things the same way we have been doing them,” he said.

“Climate change is manifesting itself in different ways such as drought, extreme heat and others.

“In recent years, when we say we had rains, we actually mean the drought was better than before!”

According to Agricultural Ministry officials, government is fast-tracking a drought management strategy that will incorporate climate change interventions such as drought-compliant planning, crops and livestock production. Other countries around the region are working on similar measures to boost resilience.

For now, however, in this hunger season, most of the 41 million will have to bank on the benevolence of increasingly reluctant strangers.