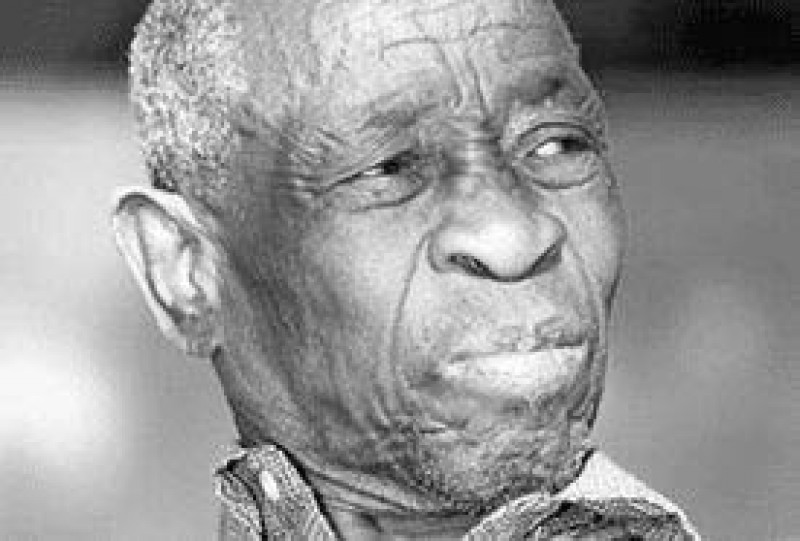

Comrade Fish: Memories of a Motswana in the ANC

Correspondent | Friday July 3, 2020 14:50

This revised edition is not an exact version of the first. There are several reasons for deciding not to simply scan and upload the first edition. One, we located an old file and transferred it from a floppy disk to a modern PC, thereby enabling us to work from one of the later drafts used in the writing of the manuscript. Two, the editor assigned to the original publication by Pula Press did a very poor job formatting the first edition, and we did not want to replicate his errors.

The new version omits the introduction and a number of footnotes from the original, and consists primarily of Fish Keitseng’s testimony. Although a few new references have been entered in the footnotes, no real attempt has been made to cite newer information that has emerged over the last 19 years. Many more details regarding various parts of Keitseng’s life and his relations with his comrades have come to light, but these details are not evident in this revised edition.

This book is based on about 30 hours of recollections recorded from Keitseng in Gaborone, December 1996-January 1997. In many ways the project unfolded from attempts made in 1994 to locate Keitseng and obtain his story, which had remained practically unknown up to that time.

The publication of Keitseng’s story in two articles the Botswana Gazette in 1994, combined with the end of apartheid, led to tremendous interest in his experiences. Over the next few years, Keitseng became anxious to complete a memoir, leading to the completion of the project as his memories were transcribed and supplemented with materials from the archival record.

Keitseng had a very vivid, though unconventional memory. Completely uneducated, although literate, he could relate stories without interruption in great detail. Often these stories were told through remembered conversations. What Keitseng lacked in his recall was context and chronology—typically he could not remember the order of events, and nor could he always explain the wider context of events he was involved in.

As a result, his interviews, once transcribed, had to be reordered. Moreover, someone of his contemporaries, such as Kenneth Koma, Michael Dingake, Rica Hodgson, and others, had to be interviewed to obtain the context of certain episodes. His recollections then, though vivid, required much editorial intervention in order to create a viable narrative.

By this stage it is well established that Keitseng’s autobiography is an authentic and accurate account of the freedom struggle. The vast majority of events that he discusses have been corroborated in police intelligence files, in other autobiographies, and in interviews with his contemporaries. His experiences continue to be cited in a range of publications. It fully deserves its spot alongside other classic Botswana memoirs from the late colonial period, accompanying those by Quett Masire, David Magang, Michael Dingake, and Motsamai Mpho.

Since the publication of Comrade Fish in 1999 he has become well known as a historical figure. Following his death in 2005, he was given a posthumous Order of Luthuli award by President Zuma of South Africa, and in the same year had his house in Lobatse declared a national monument by the government of Botswana.

Since 2005 he has been the subject of numerous newspaper articles, and an annual walk from his Lobatse house to Peleng Hill recreating his exploits with Nelson Mandela is now ongoing. In short, Keitseng is now recognised as one of Botswana’s major nationalist figures—a position he rightfully deserves despite his earlier anonymity.

Introduction

With the end of political apartheid and the African National Congress’ (ANC) rise to power in South Africa, the history of its liberation struggle can now be more fully related by its participants. Nelson Mandela has led the way with his own autobiography, which is one of several by leading ANC members. The role played by Botswana citizens within the ANC is relatively obscure, notwithstanding the publication of autobiographies by two such participants, Michael Dingake and Motsamai Mpho.

Without undermining the contributions of others, there can be no doubt that Fish Keitseng was the key Botswana citizen member of the ANC during the early 1960s. After extensive involvement in the ANC’s passive resistance campaigns of the 1950s, he was arrested by South African authorities and prosecuted in the Treason Trial, along with Mandela, Mpho, and 153 other leading ANC members.

Following his deportation to his native Bechuanaland Protectorate in 1959, he established and successfully ran an underground transit system, which funnelled ANC members from Lobatse in the southern Protectorate to Northern or sometimes Southern Rhodesia (later Zambia and Zimbabwe), from where they journeyed to Tanganyika/Tanzania. This operation was of vital importance for it enabled the ANC, along with its Congress Alliance allies, to rescue thousands of activists from the clutches of the apartheid state. This in turn allowed for the re-establishment of the organisation from exile as a liberation movement capable of ultimately assuming state power.

Keitseng’s part in this drama might have been forgotten. Until apartheid’s final demise he had neither the capacity nor desire to draw public attention to his deeds. Unlike the previously-mentioned luminaries, he never received any formal education and cannot write with great proficiency. His self-taught English is fluent but colloquial. He was, also, long viewed with suspicion, if not hostility, by Botswana authorities, who were never especially comfortable with home grown transnational freedom fighters.

His consuming commitment to the struggle, and the sometimes petty persecution that it engendered, compromised his ability to maintain employment or otherwise accumulate wealth. Being involved in underground activities he, furthermore, long valued his relative anonymity. It also seems clear that a number of past observers, having come into contact with this unlettered peasant-proletarian, simply underestimated his importance. In the existing literature Keitseng’s name is often not tied to his contributions.

Thus Kasrils, in describing his escape from South Africa in 1963, writes the following, after being picked up near Lobatse by some unnamed “comrades” in a Land Rover: We drove to a township outside Lobatse and were carried into a house, wrapped in blankets. They explained that they had to be vigilant about South African agents.... In order to travel safely to Tanzania, where the ANC had its headquarters, we needed to report our arrival to the District Commissioner.... We were granted political asylum and photographed....We spent a week [and] finally departed in a six-seater aircraft for Tanzania.

Although Kasrils does not say so, he was being looked after by Keitseng, who arranged his pickup, safe house, legal assistance, and transport over an entire week. Similarly, Annmarie Wolpe’s otherwise quite detailed account of her husband Harold Wolpe’s escape through Botswana neglects any mention of Fish. Batswana colleagues have also downplayed Keitseng’s role. Mpho, who, as we shall see, fell out with Keitseng in 1965 in the aftermath of Botswana’s first election, acknowledges him in passing, while Dingake, whose book came out in 1987, was scrupulous not to give away any information that might have compromised the still ongoing struggle.

Keitseng’s life as a migrant worker and grassroots union organiser, as well as his lack of schooling, further set him apart from most other leading ANC activists of his generation. When he initially became involved in politics he was still very much the product of his rural background, having grown up at his father’s cattlepost.

After going to South Africa just before the Second World War to work in the mines, he began to acquire a militant working class consciousness not shared by many Batswana migrants. Later leaving the mines, he stayed on to work in Johannesburg, usually without the right papers, moonlighting as both a union and ANC activist.

Yet, notwithstanding his commitment to South Africa’s liberation, Keitseng has never forgotten his roots as a son of Botswana’s soil.

If apartheid was a fire that threatened to consume his neighbour’s house, as a Motswana he knew his neighbours were his brothers and sisters. Moreover, Batswana could never be free while South Africans were enslaved.

Parallel to Keitseng’s contributions to the ANC underground, was his significant role in the promotion of both organised labour and nationalist politics inside Botswana. He was a founding father of the Bechuanaland Trade Union Congress (BTUC), as well as the People’s Party (BPP), Independence Party (BIP) and National Front (BNF).

For various reasons Keitseng, along with the above organisations, had been marginalised by the end of the 1960s, though the BNF was to emerge as Botswana’s principal opposition movement. By then the ANC presence within Botswana had, also, declined.

Members of Botswana’s relatively conservative post-colonial governments, as well as the apartheid regime, nonetheless, still kept “Comrade Fish” under surveillance. After Botswana’s independence Keitseng thus remained as something of a pariah to Botswana officialdom.

He also lived in very difficult circumstances, surviving as an unskilled labourer, while struggling to educate his children. Despite rejection and lack of material success, Keitseng was intransigent in his principled devotion to his cause. In the low income neighbourhoods of Lobatse and Gaborone where he has lived, he has always been a local hero. To go walking around with him in these communities is to gain a deeper understanding of the word “popularity”.

After years of poverty, persecution, and frustration, Keitseng has begun to receive wider recognition.

In 1989 he was elected as a Gaborone City councillor, and when Nelson Mandela came to Botswana after his release it was Comrade Fish whom he called for. Members of Botswana’s political leadership, perhaps ashamed of past slights, now treat him as a respected elder statesman.

For all his tough times, Keitseng has always retained a remarkably positive outlook on life. As he approaches his eighth decade he remains an unembittered and ever humble servant of the people, who has never considered compromising the values that he learned as a youthful activist.

An ordinary man who, through his dogged commitment, made extraordinary contributions, Keitseng has lived a life worthy of remembrance.

*Comrade Fish: Memories of a Motswana in the ANC was written by Barry Morton and Jeff Ramsay. It was originally published by Pula Press in 1999. The free ebook is available on www.https://unisa-za.academia.edu/BarryMorton