Glue and the children of the street

Lerato Maleke | Friday February 27, 2015 14:39

Street children are just like any other children. They listen, take orders, play, sing just like ordinary children.

Two main differences however: they are homeless and many of them sniff glue. The children of the streets are usually dirty, sleep in culverts and forage for food in dustbins, each carrying a sad tale of abandonment, loss, disease or neglect.

However, Patrick Mmopi and Baliki Malongwa from Old Naledi, Ditakana are slowly breaking the mould.

A Good Samaritan, Blessing James, has volunteered to help Patrick, Baliki and other children. The children of the streets now take James as a brother and love him.

For some, even the allure of glue-sniffing has somewhat dulled as James has provided the loving care that has been missing from their lives for so long.

“Nna ke a mo rata,” Patrick professes.

It is Thursday and I cross over to the Main Mall with the street children. The Good Samaritan runs an organisation known as ‘The New Africa’s Salvation’ and has promised that five street children will show up for our meeting.

After a long wait, only 18-year-old Patrick and 21-year-old Baliki show up. It turns out that Mochudi police nabbed Baliki’s brother, who is also a street child, in the morning after the two had a physical fight.

“We fought because he was insulting my grandmother,” Baliki says unapologetically.

Unlike other street children, Patrick and Baliki are technically not homeless. In fact, they have a family home in Old Naledi where they sleep every night. They, however, return to roam the streets during the day, continuing the lifestyle they were introduced to by their brothers.

Lured by the apparent ease of the lifestyle, the two teenagers jumped at it, only to become hooked on glue and fully dependent on the streets.

It is 10am, but Baliki already appears high on glue. A normal day for the two boys involves washing vehicles for cash and begging for coins.

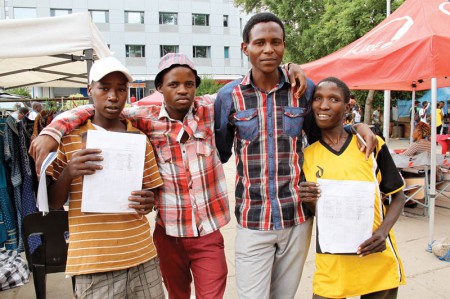

Today, they are bathed and dressed smartly, but they still have the ‘look’ of the streets on them.

Patrick and Baliki cannot exactly remember when they dropped out of school. They both agree they were doing form 2, but further details are clouded by the years of tough living.

“Go lobaka tota,” says Patrick.

“Mma! I want to go back to school. I’d like a boarding school so that I can be far from home.

“I am tired of always sniffing glue and I want to go back to school.”

As he speaks, he retrieves a juice box from under his T-shirt. With a shy look on his face, he takes a few sniffs and smiles.

Two police officers pass nearby and James threatens to report him to them. Patrick promptly puts the juice box away, within reach however.

Baliki on the other hand, is slowly gravitating towards a different planet. He appears disoriented and spacey. He is failing to pronounce his words properly, but insists on speaking in English despite this.

He too wants to return to school, preferably boarding, where he says he would be forced to give up glue-sniffing.

“When I grow up I want to work for CEDA and use a laptop,” he says, to titters from Patrick.

“Wareng? O ka bereka mo CEDA o tagilwe ke glue o kare o avocado e botlhoko jaana,” Patrick says dismissively.

He adds: “I want to be a pilot or a policeman or a teacher.” Taking a sniff of glue he attempts to continue speaking, but James interrupts with a strong warning about the drug-taking.

Patrick explains that his mother passed away three years ago and he is staying with relatives and his granny. Baliki’s mother, on the other hand, is alive and well, living in Old Naledi.

“My sister is married in South Africa, but I never visit her,” he says.

Our conversation is slowly reaching its end.

The two teenagers ask me for clothes.

“Ga re na dilwana. Tlhe mma o re tlele diaparo tsa ngwana wa gago ka moso le ene o tle le ene re mmone,” says Patrick.

Oratile Modisane, a middle-aged hawker at the Main Mall, recalls first seeing the two teenagers about six years ago.

“I saw them eating from a dustbin and warned them it was unhealthy for them. They stopped.

“I remember it was winter and very cold. I gave one of them a tracksuit I was selling,” she says.

Modisane says from there the boys started gathering at her stall and even invited others.

“I bought them breakfast, lunch and supper up to now and they know that I am like a mother to them,” she explains.

According to the Mochudi woman, former Parliament speaker, Margaret Nasha took a number of street children and taught them how to plant and sell flowers. It is apparent that few held on to the lessons they learnt.

Modisane, however, believes the blame for the children’s plight should be placed squarely at their parents’ door.

“These children are obedient, they listen. The parents don’t take care of their children.”