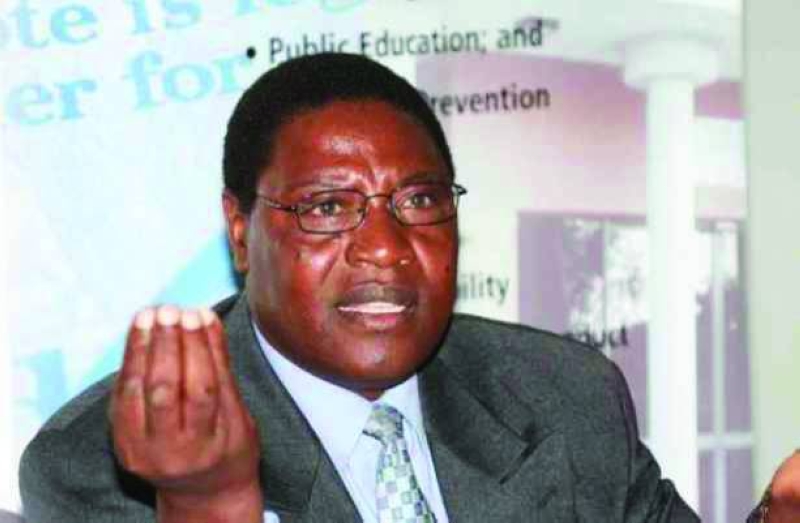

Magosi is responsible for my humiliation –Katlholo

Mpho Mokwape | Monday May 5, 2025 06:00

He says that the Director General of the Directorate of Intelligence and Security (DIS), Magosi, is absolved from liability was untenable because, as the superior he remains accountable for wrongful acts committed by DIS employees within the scope of employment. He was surrounded by controversy before his suspension in June 2022 for daring to investigate the DIS boss, Magosi.

“Any assertion that immunity, prescription, or procedural technicalities absolve Magosi from liability is untenable. The Attorney General as legal representative of Magosi cannot escape responsibility merely because they are not the direct actors,” said Katlholo.

The former DCEC DG filed a lawsuit sometime in May 2023 against then Attorney General, Advocate Abraham Keetshabe, Director General of DIS Magosi, spy agency spokesperson Edward Robert, DCEC lead investigating officer Jet Mafuta, and acting Director General of DCEC, Tshepo Pilane, citing malicious and defamatory utterances by the above-mentioned.

In his suit, Katlholo demands damages from the state for what he alleges as statements made by the defendants that were deliberately malicious and intended to injure his good name and reputation. Recently, appearing in court, Katlholo, through his attorney, Dutch Leburu said the objections raised by the defendants attempt to rely on technical deficiencies that either misinterpret statutory provisions or apply them inappropriately to the facts of the case.

In the filed heads of argument, Katlholo submitted that the argument that no cause of action has been disclosed against the AG, Magosi, and Pilane fails to acknowledge the fundamental basis of vicarious liability. (In law, vicarious liability means a person (typically an employer) is held responsible for the wrongful acts of another person (typically an employee) who is acting within the scope of their employment. This responsibility arises, not from the initial person's actions, but from their control and influence over the employee.)

“The defendants fail to acknowledge the fundamental basis of vicarious liability. AG, as the legal representative of Magosi, cannot escape responsibility merely because they are not the direct actor. The defendants contend that the plaintiff’s failure to serve Statutory Notice on Robert and Mafuta is fatal to the claim. However, this objection is misplaced, as these parties are merely nominal plaintiffs, and no relief is sought against them,” argued Katlholo.

He explained that serving notice upon them is therefore unnecessary and irrelevant to the substantive claim against Magosi and that the argument that Robert and Mafuta lack standing because they acted on behalf of the government. He said this overlooks the fundamental principle that public officers do not enjoy blanket immunity from civil liability.

Additionally, he said that since these defendants are cited in a nominal capacity, their standing is not a decisive factor in the action and that the assertion that the Plaintiff's claim has prescribed lacks merit as prescription does not automatically extinguish liability where the wrongful act remain actionable against the principal employer.

“The defendants rely on statutory provisions, including Section 61 of the Police Act and Section 24 of the Intelligence and Security Act, to argue that claims against certain defendants are barred. However, these provisions do not extend to protecting Magosi from vicarious liability, rendering the objection irrelevant.

Ultimately, Katlholo said his claim is legally and procedurally sound emphasising that the objections raised are either misplaced, misinterpret legal principles, or seek to impose unnecessary procedural hurdles to frustrate the Plaintiff's right to seek redress.

On the liability of AG and Magosi

Katlholo stated that the AG has been cited in these proceedings in his capacity as the legal representative of the Government of Botswana, in compliance with Section 3 of the State Proceedings (Civil Actions by or against Government or Public Officers) Act, which provides: 'Except as may otherwise expressly be provided by any law, actions by or against the Government shall be instituted by or against the Attorney-General.'

He pointed out that the argument that no cause of action has been disclosed against him disregards the statutory framework governing litigation against the government, and his joinder in these proceedings is legally mandated.

Katlholo noted that the principle of vicarious liability is firmly entrenched in the law as explained that “An employer is made liable for the wrongs committed by his or her servant in the course and scope of the servant's employment. The employer need not be personally at fault in any way, but the wrong of the servant (for which the servant remains personally liable) is imputed or transferred to the employer, who often has the 'deeper pocket' or 'broader financial shoulders' to compensate the injured party”.

“To establish a claim based on vicarious liability, the plaintiff must plead and prove the following elements: That the individual who committed the wrongful act was an employee of the Defendant; The scope of the employee's duties at the relevant time; and that the wrongful act was committed in the course and scope of the employee's employment,” he said.

According to him, his declaration explicitly alleges the above elements, thereby sufficiently disclosing a cause of action against Magosi and that the mere fact that he was not the direct actor does not absolve them of liability, as vicarious liability imputes the wrongful acts of employees to their employer.

Katlholo averred that he defendants' exception is legally untenable as it improperly challenges the truth of his allegations rather than addressing whether the claim is legally sustainable. “The plaintiff has set out the factual and legal basis for the claims against AG and Magosi. The exception should therefore be dismissed with costs,” he said.

On whether or not the failure to serve a Statutory Notice on Robert and Mafuta is fatal to his case?

Katlholo explained that the State Proceedings Act Section 4 of the State Proceedings (Civil Actions By or Against Government or Public Officers) Act provides that: 'No action shall be instituted against the Government, or against a public officer in respect of any act done in pursuance, or execution, or intended execution of any law, or of any public duty or authority, or in respect of any alleged neglect or default in the execution of any such law, duty or authority, until the expiration of one month next after notice in writing has been, in the case of the Government, delivered to or left at the office of the Attorney-General, and, in the case of a public officer, delivered to him or left at his Office, stating the cause of action, the name, description and place of residence of the plaintiff and the relief which he claims.'

“From the foregoing, it is clear that before suing a public officer regarding anything done in their official capacity, one has to deliver to the officer a Statutory Notice of intention to sue. It is also not disputed that Robert and Mafuta were not served with a Statutory Notice before litigation commenced,” he said.

According to the heads Katlholo mentioned that submission to the defendants' objection is threefold saying firstly, there has been substantial compliance with the requirements of the States Proceedings Act, and that strict compliance should not be assessed in a rigid or overly formalistic manner.

Special Pleas by Robert and Mafuta, the former DCEC said the pair have raised a special plea, contending that they were not served with the originating process in these proceedings and argue that, as a result, the one-year prescription period applicable to defamation claims has elapsed, rendering the plaintiff's claim prescribed.

Katlholo disputed that saying contrary to the defendants' assertion, he duly served the writs of summons albeit though AG and furthermore, both defendants entered an appearance to defend the action, demonstrating their awareness of and participation in the proceedings.

He pointed out that a proper interpretation of the Prescription Act supports the conclusion that the claim has not prescribed. This is because prescription cannot operate against one co-debtor while remaining valid against another. Section 9 of the Prescription Act provides that: 'Prescription shall not be affected in respect of one joint debtor by any fact which would affect prescription in respect of any other joint debtor, except in the case of debtors liable in solidum.'

“It is a well-established principle that in cases of vicarious liability, an employer held liable for the wrongs of an employee is bound in jointly with that employee meaning that the employer's liability is inseparable from that of the employee, and prescription against one party does not necessarily extinguish the claim against the other,” he said.

In conclusion Katlholo said in light of the foregoing, the employer being Magosi cannot rely on statutory defences’ available to individual employees to evade vicarious liability.

Furthermore, that the immunity under Section 24 of the Intelligence and Security Act does not apply in this context, as the claim is directed at the employer, not the individual officer.

In addition, he said his allegations of malice and lack of reasonable suspicion necessitate a full trial to assess whether the statutory immunity is applicable.