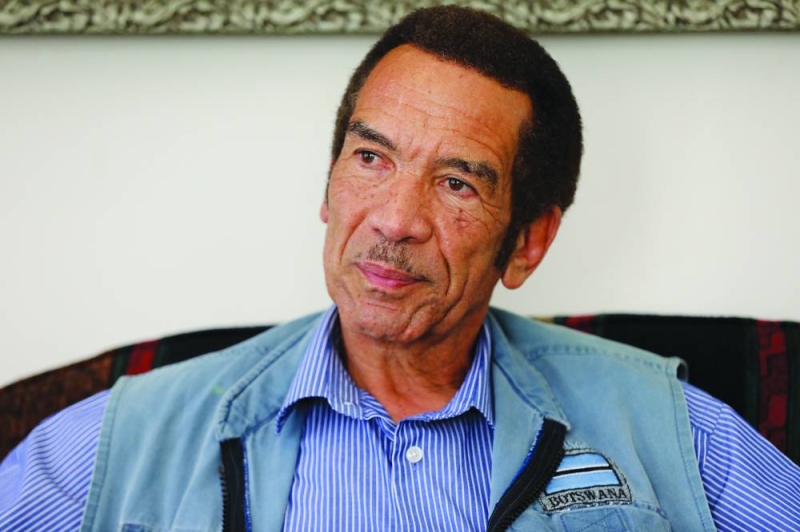

Khama loses

Goitsemodimo Kaelo | Tuesday May 30, 2023 06:00

Khama, who is facing criminal charges in Botswana, had moved swiftly and approached the South African court with a view to block his ‘impending’ extradition following the issuance of a warrant of arrest by a local magistrate in December 2022.

This is despite the fact that Botswana is yet to lodge an extradition request with the South African government, where Khama has been exiled for over two years allegedly in fear for his life.

In his view, he says a request for his extradition is imminent. However, his attempt was dealt a blow last Wednesday when the South African High Court in Johannesburg dismissed his application seeking an order that section 5(1) (b) permits a magistrate seized with an application for an arrest warrant to consider representations by a person whose arrest is sought before the issuing of the warrant.

The court also ruled against Khama by rejecting his plea to declare the section 5(1)(b) unconstitutional. Additionally, the court also ruled in favour of the Director of Public Prosecutions, Gauteng Local Division, Deputy Director, and National Director of Public Prosecutions who are cited as first, second and third respondent respectively in the matter by granting an order with costs to strike out paragraphs 64 to 143.3 of the applicant’s founding affidavit.

In these paragraphs, Khama had outlined the intended representations he would wish to present to the magistrate should a warrant for his arrest be sought in the future as well as factual detail about the circumstances leading up to his departure from Botswana, which the South African prosecution considered irrelevant, unnecessary and bordering on an abuse of the court process.

In his application, the former president was seeking a declaratory order to the effect that, properly interpreted, section 5(1)(b) permits a magistrate seized with an application for an arrest warrant under that section, in appropriate circumstances, to consider representations by a person whose arrest is sought before the issuing of the warrant. In the alternative, and if this court rejects the applicant’s interpretation of s 5(1) (b), he sought an order declaring section 5(1)(b) unconstitutional to the extent that such authorisation is not implicit in the provision.

His final prayer was for an order directing that any of the respondents who intend to make an application for a warrant for the applicant’s arrest must provide the applicant through his attorneys with reasonable notice of that application.

However, the court ruled that the law does not permit a magistrate to consider representations before issuing a warrant of arrest. In a case which was presided over by a panel of three judges, they found that “in our view, not only does the applicant’s interpretation in this case unduly strain the language of section 5(1) (b); it goes further and upends the entire scheme of the Act”.

The judges said for Khama to read section 5(1) (b) as permitting a magistrate to consider or call for representations before issuing a warrant of arrest would defeat the purpose of the entire Act. “It would provide a Magistrate with the authority to decide whether the extradition process should proceed. It would impermissibly widen the limited discretion of the magistrate, as envisaged in section 5(1)(b), and expropriate to the Magistrate powers that lied within the prerogative of Minister,” read the judgment in part.

“We conclude that given the text, the context and the purpose of sections 5(1) (b), read with section 39(2) of the Constitution in mind, there is no room for a finding in terms of which it is declared by this Court that section 5(1) (b) of the Act authorises a Magistrate seized with an application for an arrest warrant to permit and consider the making of representations by a person before the Magistrate issues a warrant for the arrest of that person in appropriate circumstances.” Khama’s application followed an exchange between his attorneys and the Director of Public Prosecutions, Gauteng Local Division in which the latter had turned down his plea to be afforded an opportunity to submit representations to the appointed magistrate before any warrant for his arrest under section 5(1)(b) of the Act was issued.

It is said that Khama’s attorneys had written to the South African Director of Public Prosecutions last year stating that it had come to their attention that a possibility exists that South Africa may receive a request from Botswana for the applicant’s extradition. Whilst he stated in the said letter that he would cooperate fully with all future extradition proceedings that may be instituted, he said any efforts to arrest and detain him would be inappropriate, unreasonable, unlawful, and unconstitutional.

However, Deputy Director of Public Prosecutions, Gauteng Local Division, Johannesburg responded that the request could not be agreed to due to the fact that there is no provision of (sic) such a procedure in the Extradition Act No. 67 of 1962. According to the court papers, Khama avers that he understands that, as part of the onslaught against him, Botswana intends to seek his extradition on what he says are “trumped-up, fabricated charges”. As such, should he be arrested in South Africa or extradited to Botswana, he will be persecuted for his political views, putting his life and bodily integrity at risk.